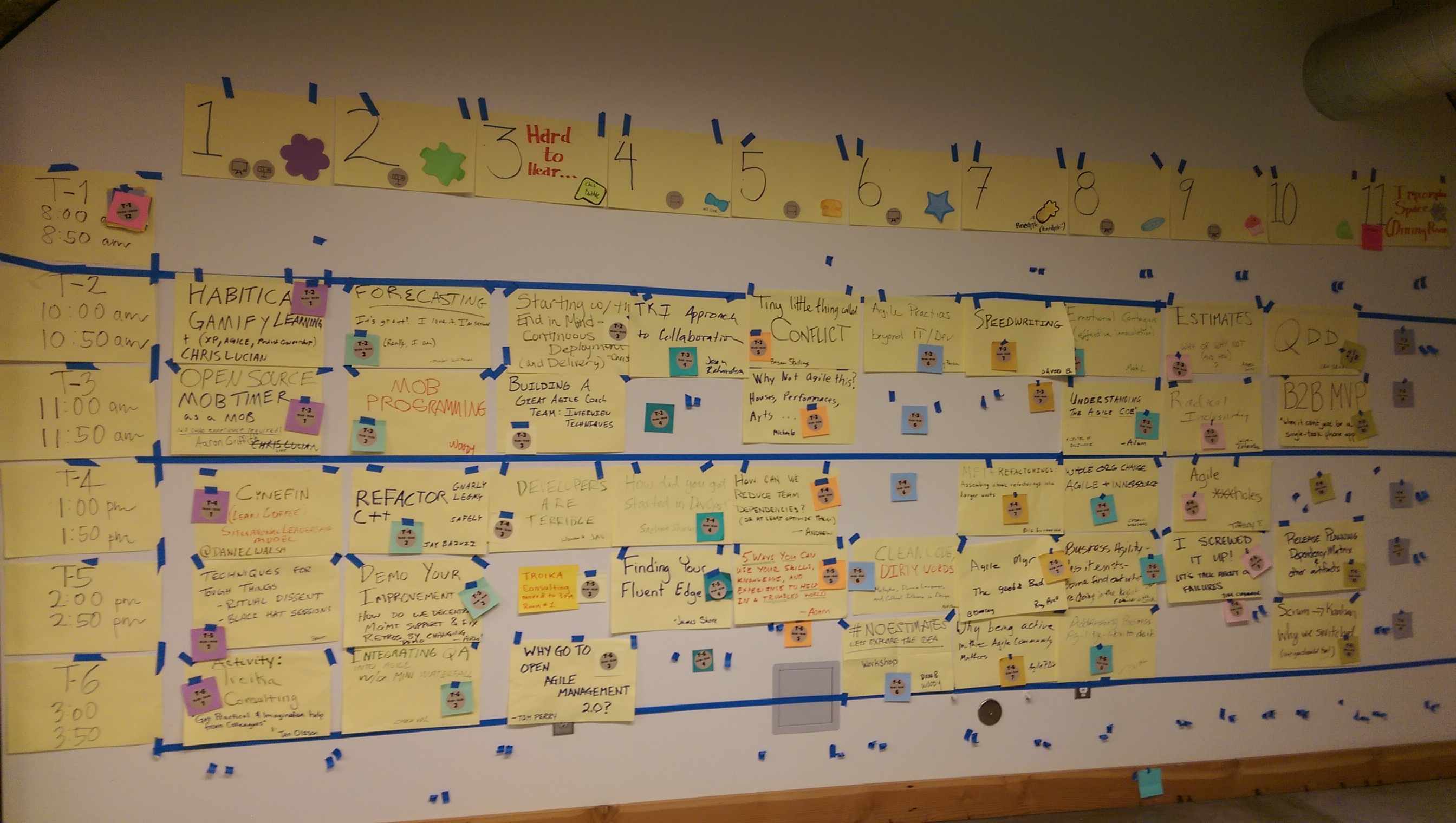

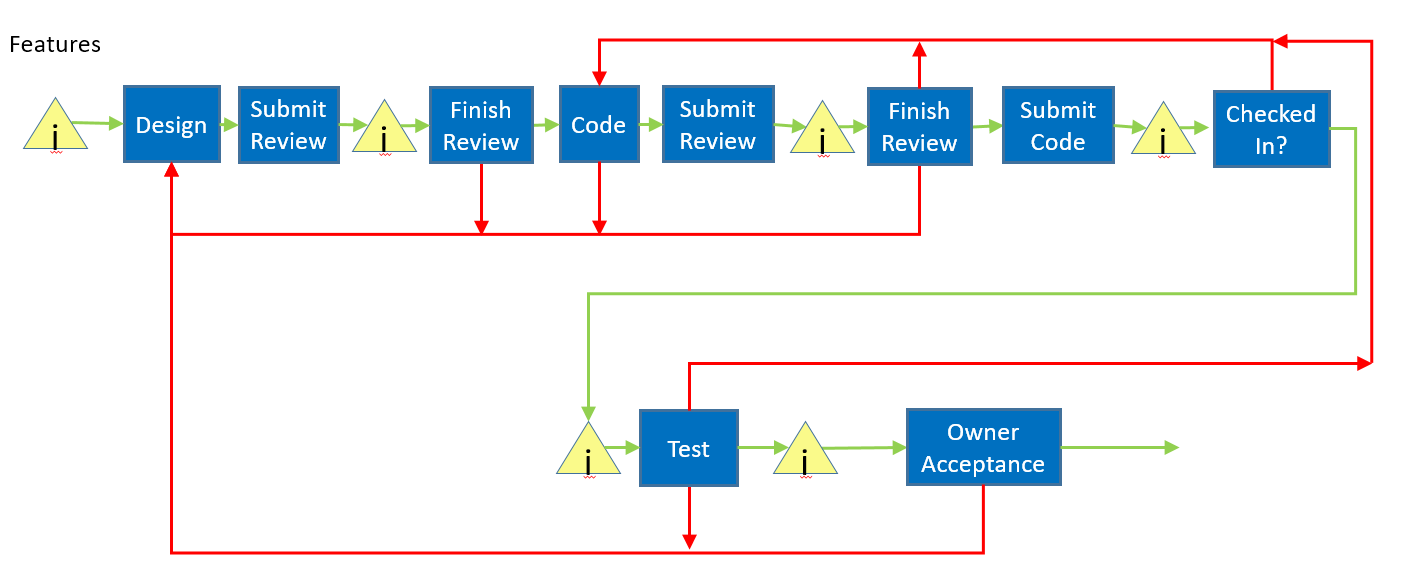

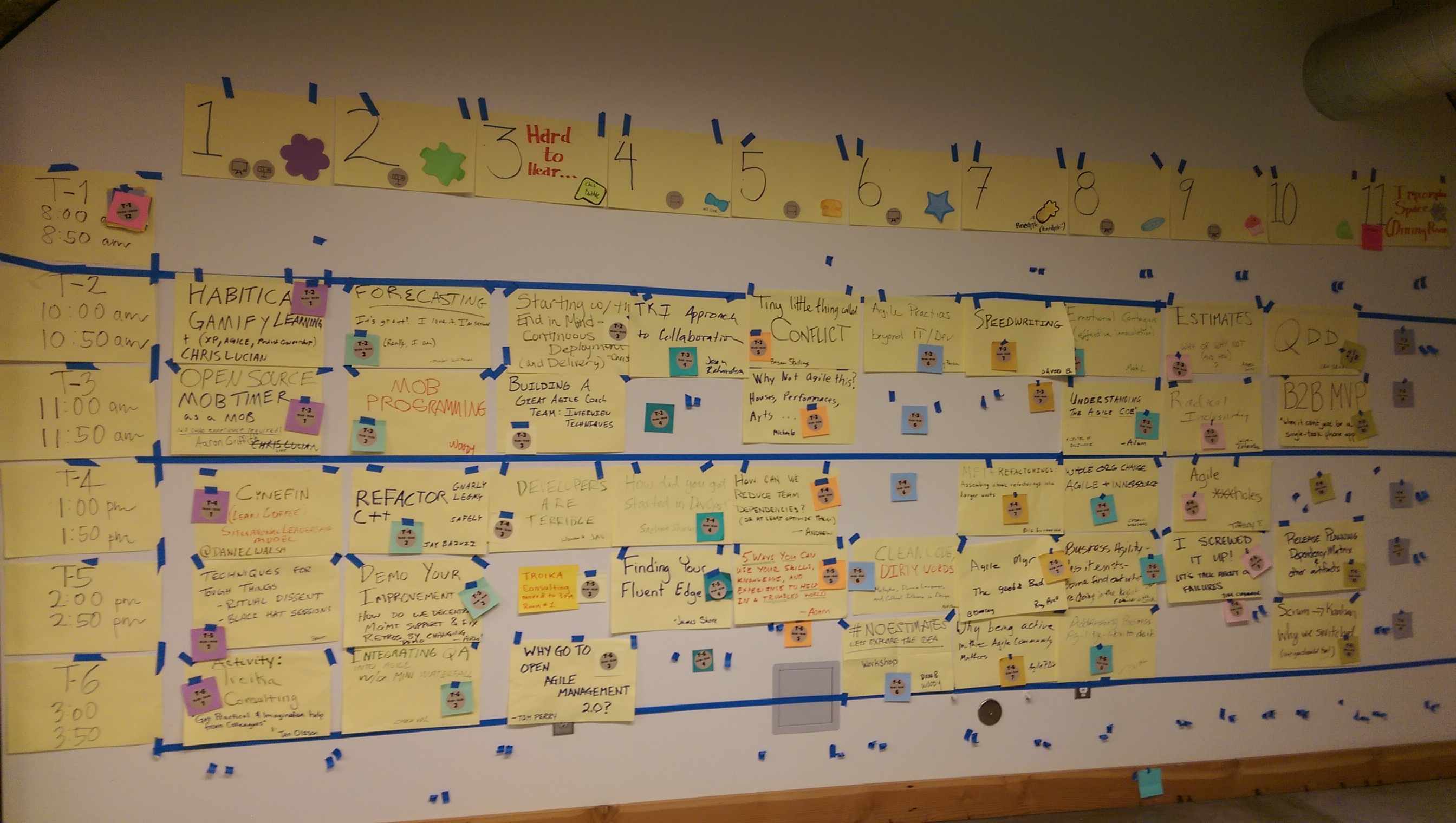

Agile Open Northwest uses a different approach for running a conference. It is obviously around agile, and there is a theme – this year’s was “Why?” – but there is no defined agenda and no speakers lined up ahead of time. The attendees – about 350 this year – all show up, propose talks, and then put them on a schedule. This is what most of Thursday’s schedule looked like; there are 3 more meeting areas off to the right on another wall.

I absolutely love this approach; the sessions lean heavily towards discussion rather than lecture and those discussions are universally great. And if you don’t like a session, you are encouraged/required to stand up and go find something better to do with your time.

There are too many sessions and side conversations that go on for me to summarize them all, but I’ve chosen to talk about four of them, two of mine, and two others. Any or all of these may become full blog posts in the future.

TDD and refactoring: Did we choose the wrong practice?

Hosted by Arlo.

The title of this talk made me very happy, because something nearly identical lived on my topic sheet, and I thought that Arlo would probably do a better job than I would.

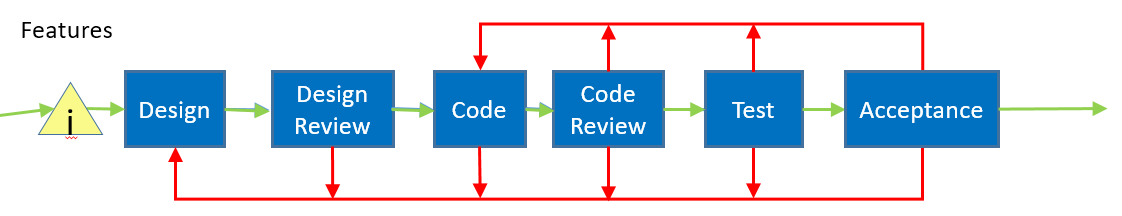

The basic premise is simple. TDD is about writing unit tests, and having unit tests is a great way to detect bugs after you have created them, but it makes more sense to focus on the factors that cause creation of bugs, because once bugs are created, it’s too late. And – since you can’t write good unit tests in code that is unreadable – you need to be able to do the refactoring before you can do the unit testing/TDD anyway.

Arlo’s taxonomy of bug sources:

- Unreadable code.

- Context dependent code – code that does not have fixed behavior but depends on things elsewhere in the system

- Communication issues between humans. A big one here is the lack of a ubiquitous single language between customers to code; he cited several examples where the name of a feature in the code and the customer visible name are different, along with a number of other issues.

I think that the basic problem with TDD is that you need advanced refactoring and design skills to deal with a lot of legacy code to make it testable – I like to call this code “aggressively untestable” – and unless you have those skills, TDD just doesn’t work. I also think that you need these skills to make TDD work well even with new code – since most people doing TDD don’t refactor much – but it’s just not evident because you still get code that works out of the process.

Arlo and I talked about the overall topic a bit more offline, and I’m pleased to be in alignment with him on the importance of refactoring over TDD.

Continuous Improvement: Why should I care?

I hosted and facilitated this session.

I’m interested in how teams get from whatever their current state to their goal state – which I would loosely define as “very low bug rate, quick cycle time, few infrastructure problems”. I’ve noticed that, in many teams, there are a few people who are working to get to a better state – working on things that aren’t feature work – but it isn’t a widespread thing for the group, and I wanted to have a discussion about what is going on from the people side of things.

The discussion started by talking about some of the factors behind why people didn’t care:

- We’ve always done it this way

- I’m busy

- That won’t get me promoted

- That’s not my job

There was a long list that were in this vein, and it was a bit depressing. We talked for a while about techniques for getting around the issue, and there was some good stuff; doing experiments, making things safe for team members, that sort of thing.

Then, the group realized that the majority of the items in our list were about blaming the issue on the developers – it assumed that, if only there wasn’t something wrong with them, they would be doing “the right thing”.

Then somebody – and of course it was Arlo – gave us a new perspective. His suggestion was to ask the developers, “When you have tried to make improvements in the past, how has the system failed you, and what makes you think it will fail you in the future?”

The reality is that the majority of developers see the inefficiencies in the system and the accumulated technical debt and they want to make things better, but they don’t. So, instead of blaming the developers and trying to fix them, we should figure out what the systemic issues are and deal with those.

Demo your improvement

Hosted by Arlo.

Arlo’s sessions are always well attended because he always comes up with something interesting. This session was a great follow-on to the continuous improvement session that I hosted.

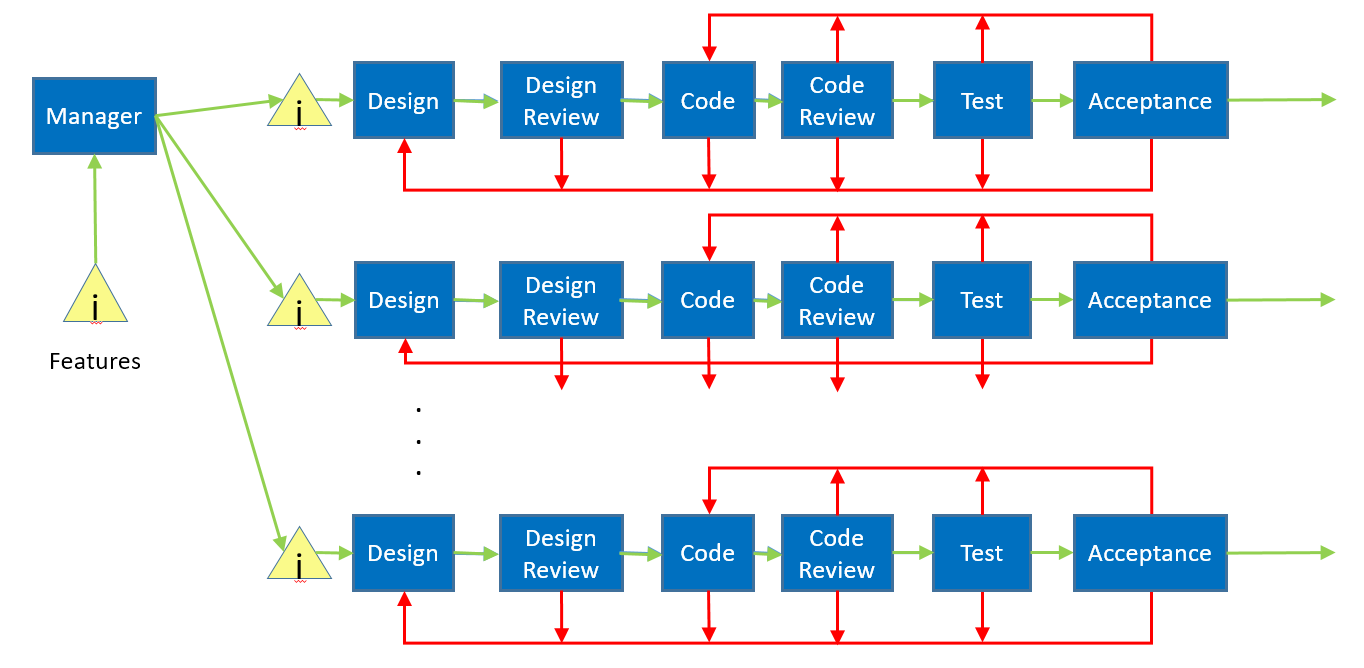

Arlo’s basic thesis for this talk is that improvements don’t get done because they are not part of the same process as features and are not visibly valued as features.

For many groups, the improvements that come out of retros are either stuck in retro notes or they show up on the side of a kanban board. They don’t play in the “what do I pick up next” discussion, and therefore nothing gets done, and then people stop coming up with ideas it seems pointless. His recommendation is to establish second section (aka “rail”) on your kanban board, and budget a specific amount to that rail. Based on discussions with many managers, he suggested 30% as a reasonable budget, with up to 50% if there is lots of technical and/or process debt on the team.

But having a separate section on the kanban is not sufficient to get people doing the improvements, because they are still viewed as second-class citizens when compared to features. The fix for that is to demo the improvements the same way that features are demo’d; this puts them on an equal footing from a organizational visibility perspective, and makes their value evident to the team and to the stakeholders.

This is really a great idea.

Meta-Refactoring (aka “Code Movements”)

Hosted by me.

In watching a lot of developers, use refactoring tools, I see a lot of usage of rename and extract method, and the much less usage of the others. I’ve have been spending some time challenging myself to do as much refactoring automatically with Resharper – and by that, I mean that I don’t type any code into the editing window – and I’ve developed a few of what I’m thinking of as “meta-refactorings” – a series of individual refactorings that are chained together to achieve a specific purpose.

After I described my session, to friend and ex-MSFT Jay Bazuzi, he said that they were calling those “Code Movements”, presumably by analogy to musical movements, so I’m using both terms.

I showed a few of the movements that I had been using. I can state quite firmly that flipchart is really the worst way to do this sort of talk; if I do it again I’ll do it in code, but we managed to make it work, though I’m quite sure the notes were not intelligible.

We worked through moving code into and out of a method (done with extract method and inlining, with a little renaming thrown in for flavor). And then we did a longer example, which was about pulling a bit of system code out of a class and putting it in an abstraction to make a class testable. That takes about 8 different refactorings, which go something like this:

- Extract system code into a separate method

- Make that method static

- Move that method to a new class

- Change the signature of the method to take a parameter of it’s own type.

- Make the method non-static

- Select the constructor for the new class in the caller, and make it a parameter

- Introduce an interface in the new class

- Modify the new class parameter to use the base type (interface in this case).

Resharper is consistently correct in doing all of these, which means that they are refactorings in the true sense of the word – they preserve the behavior of the system – and are therefore safe to do even if you don’t have unit tests.

They are also *way* faster than trying to do that by hand; if you are used to this movement, you can do the whole thing in a couple of minutes.

I asked around and didn’t find anybody who knew of a catalog for these, so my plan is to start one and do a few videos that show the movements in action. I’m sure there are others who have these, and I would very much like to leverage what they have done.

Recent Comments